This rabbi gig. People have no idea what it’s all about.

That’s the tag line that Catherine deCuir and I decided to use for our novel, The Rabbi Finds Her Way. I didn’t write it, and neither did Catherine. Our protagonist, Rabbi Pearl Ross-Levy, wrote it herself.

Other than two musical theatre pieces (which are more like plays, really) and the lyrics to a number of songs (which are more like poetry), I’d never written much fiction prior this novel.

I can pinpoint the exact moment when the idea for Rabbi came about. I was sitting next to Catherine during a Temple Sinai Saturday morning Shabbat service featuring (starring?) a young boy or girl—I can’t remember which. At some point, while the kid’s parents were extolling his or her virtues, I leaned over to Catherine and whispered, “In the movie version of this service…” I have no idea the remainder of my comment, but Catherine laughed. Score one point for me.

Without knowing it, I had opened the door to an endless stream of imaginary dialogue, comments, retorts, and bar mitzvah-related machinations that had been brewing for decades—probably since my own bar mitzvah many years before.

There’s a good chance that you have attended a bar or bat mitzvah, but just to make things clear, the plural of the term is b’nei (also spelled b’nai) mitzvah, unless you are referring to multiple female ceremonies, which is b’not mitzvah. It is a coming-of-age ritual in Judaism that is generally held on the first Shabbat (Sabbath) following the birthday on which the child reaches the eligible age. A number of religious sources, including the Talmud and the Mishnah, list the age as 13 for boys and 12 for girls, although like many things Jewish, it’s more complicated than that.

As I have discussed in my book What I Wish My Christian Friends Knew About Judaism, the practice of the bar mitzvah has evolved through the centuries, and you are welcome to research it further if you wish.

In a large congregation, there is often a b’nei mitzvah ritual as part of the Saturday morning service, with one or more young people being called to the bimah, and so it is at the congregation to which I belong. Temple Sinai in Oakland, California is a Reform congregation, and our synagogue tradition places a great emphasis on this coming-of-age ritual and family participation during the service. This participation might be less-so in other congregations; I have personally observed and/or participated in hundreds of b’nei mitzvah that run the gamut between minimal and maximal emphasis.

How any ritual is conducted depends on a variety of factors—the tradition of the congregation, the makeup and desire of the participants, and the direction of the clergy, particularly the rabbi.

As with any clergy member, the rabbi injects a special style into each aspect of a congregant’s life, and so it was with our fictional rabbi who was now evolving in our imaginations.

The decision to make our rabbi female was not extraordinary. In the Reform movement the percentage of female rabbinical students had grown to more than two-thirds by 2007. Since most of the services that Catherine and I attend are led by a female rabbi, it was no giant leap to imbue our fictional character with female attributes. (Note: In response to questions by many friends, we assure them that although our fictional rabbi might have been inspired by a real person, she was not based upon her.)

Introducing a young fictional character into the world of Judaism offers an author countless opportunities for creation and invention. One example would be the drash that they might typically offer at their b’nei mitzvah. A drash is a type of sermon based on the Torah reading of the day. A good example might be based on the story of Noah and the Ark. For a moment, put aside your adult conception of Noah’s story and instead try to picture it through the mind of a thirteen-year-old. Who fed the animals? Where did Noah and his wife sleep? King-sized bed or twins? What did everyone eat for breakfast? Where were the dinosaurs and unicorns? Were Noah’s kids ark-schooled?

At some point, Catherine and I actually decided to write a book. But before we composed a single paragraph we first spent six months preparing to write—we first needed to establish the characters’ back stories and a comprehensive time line. This process will be familiar to any of you who have written fiction.

Where did our rabbi grow up, who were her friends, her parents? Is she married? How do we handle her sexuality? What does she look like? Where did she go to high school? What was her undergraduate major in college? Does she have siblings? How did her interest in religion come about? Was she always an observant Jew? What about her parents? Did she play any sports? And so on.

As we attempted to answer each question, the character became more and more clear. Her mother’s profession as a psychologist and counselor led her to meet a girl who would become her lifetime best friend. The friend’s physical condition after a serious accident and her being an observant Catholic opened the doors for many valuable plotlines.

We decided to introduce the rabbi’s love interest/future husband early in the book, and her father’s job as a university professor gave us an opportunity to introduce the young man. (Hey, our rabbi wasn’t about to marry any old schlub!)

We decided early on that the rabbi would carry some personal baggage, and after tossing around options (including diabetes, heart and lung issues, and Tourette’s syndrome), we decided on nyctophobia, a common condition characterized by fear of the dark. (Catherine reminds me that this was not a serious enough condition for some of our readers, but that’s how some people are.)

We decided that Pearl would have one sister, who turned out to be a professional musician and a lesbian. Why not?

Our own congregation (and society in general) includes a significant percentage of LGBTQ adults, so it wasn’t too far a leap to introduce a gay executive director. Black, Latino, and Asian characters all play roles in our narrative.

The naming of characters in a book of fiction always presents a challenge, we found. Catherine and I decided to name the rabbi and her sister after our own mothers, to whom we dedicated the book.

I mentioned earlier that we spent six months in preparation before beginning the narrative. What did we do during that period? Answer: we worked on a ten-year timeline that incorporated real and fictional historical events, and most important of all, the timing of Torah readings and Jewish holidays during the calendar year. Why? If we wanted a particular service to be focused around the reading of, say, Noah’s Ark, we needed to make sure that Torah portion, which appears in the book of Genesis, falls at an appropriate time during the arc of our story. To put it another way, Christmas does not fall in July, and neither does Hanukkah.

When our rabbi, Pearl, first meets her future husband, Jack, is she wearing a tight black dress, sitting on a bar stool with her legs crossed? Wrong! Instead, they meet at an open house in the faculty glade of the UC Berkeley campus, near the building where I myself attended classes. And when she suggests a restaurant for their first date, is it Chez Panisse? No. Rather, it is Los Cantaros, a neighborhood taqueria near Lake Merritt (where Catherine and I have eaten for years).

When an unnamed dry cleaner ruins one of Pearl’s black pantsuits, her mother recommends the French Cleaners in Berkeley, (where I’ve been on a first-name basis with the owner for 30 years). And when it’s time for Millie, one of our favorite septuagenarian characters, to buy a car over the phone while recuperating from surgery at a local hospital, she naturally calls the local Toyota dealer on Broadway in Oakland (where I bought my Camry).

(Let it be noted that our favorite servers at Los Cantaros, the owner of the French cleaners, and the Toyota dealer all received complimentary copies of our book.)

Writing a first book of fiction comes with a set of do’s, don’ts, and restrictions. Although Catherine and I are not unknown writers, this was our first novel, and the New York Times Bestseller List may as well have been in a far-flung Star Trek galaxy. But as I learned in 2000 after the publication of my first book and much research into book promotion, most books are sold one by one, hand-to-hand, and through endless book events and word of mouth.

After receiving our first draft of the new novel, our publisher—who encouraged my second book, On God’s Radar: My Walk Across America as well and published the second edition of What I Wish My Friends Knew About Judaism—decided the manuscript was too long, which led us to cut 30,000 words.

We justified this at the time by planning to put much of this edited material into the second volume—five volumes were originally planned. But life (and Covid-19) got in the way. Had we introduced a worldwide pandemic in our first novel, the book’s category would have quickly changed to science fiction or disaster fiction. Yet the second volume, while already half-written, might never appear in book form. It’s really no one’s fault, especially our fictional rabbi’s.

Here’s something about fiction writing that surprised the hell out of me:

At some point in the writing process, the characters begin to not only speak to you, but they begin to create their own dialogue.

Early on, I’d often ask Catherine, “So, what does Pearl say now?”

We’d knock it around and come up with something the Rabbi might say. But eventually, Pearl would answer the question herself.

And so it went with other characters, who began to speak not only in dialogue and situation, but in dialect and style. This was most apparent in conversations between the rabbi and her young protégé, a precocious 12-year-old Chinese-American bat mitzvah student. (All this is fine, except when the characters wake you up in the middle of the night and you have to write down what they’re saying. They don’t seem to sleep like normal people.)

At one point we realized that in spite of several love scenes—or perhaps because of them—our book is appropriate for young adults. (One of our favorite readers is a teenage girl whose mother told us she’s read the book more than once, and leaves it around the house for easy access.)

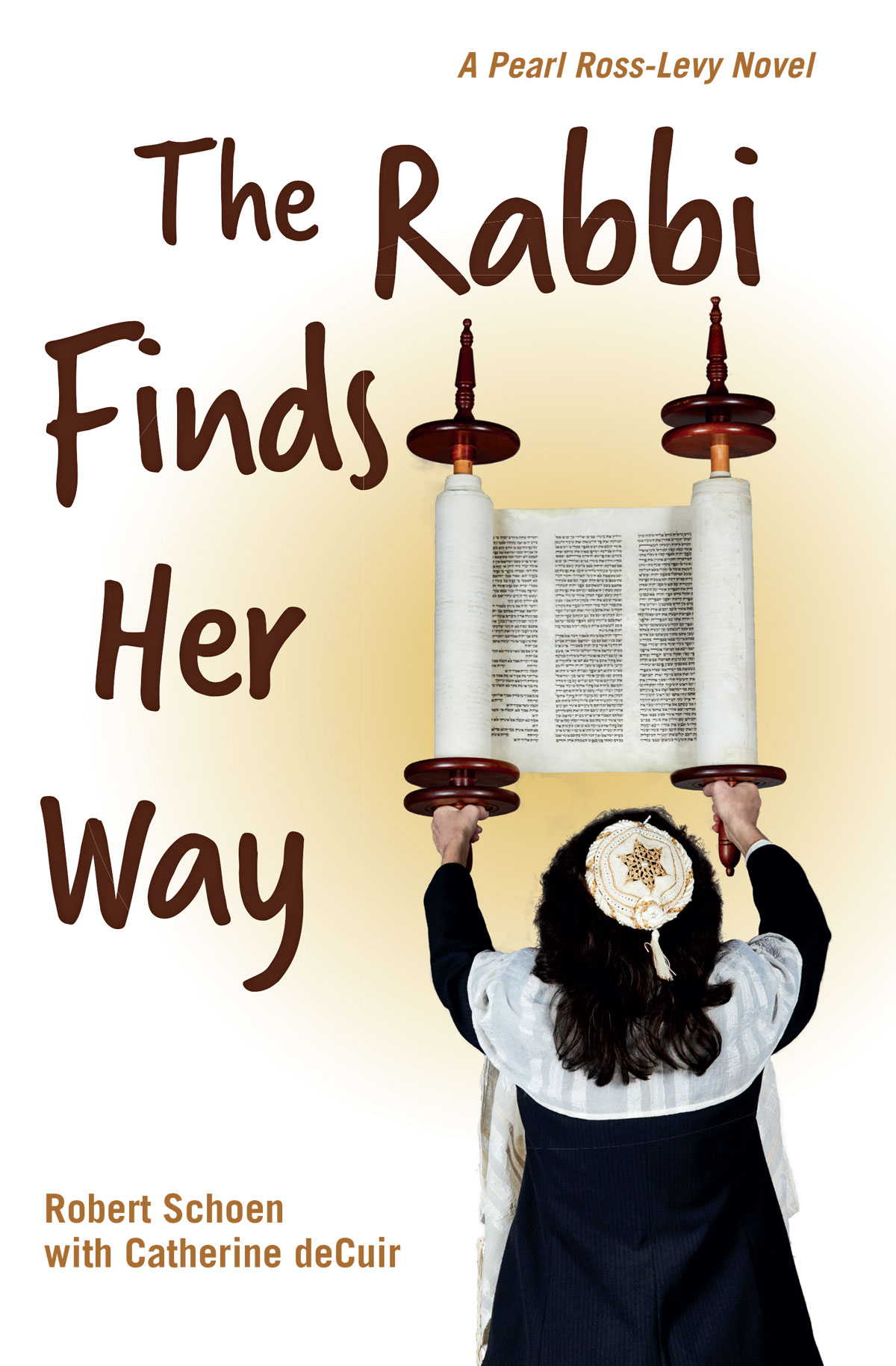

We’ve been asked many times about the cover of our book (pictured above). No, that is not any real rabbi, known or unknown. While the model’s identity shall remain a secret (psst…it’s Catherine), the source of the Jewish objects in the photo is interesting. Since our model would be required to hold the Torah scroll above her head while our professional photographer (my good friend, James Au) took the shot while standing on a ladder, it necessitated using the smallest and lightest of the several Torahs in the synagogue ark. (Catherine, a seasoned actor, prepared for this feat by doing weeks of dumbbell curls and overhead triceps extensions.)

The choice of a dark blazer was a given, but we needed a contrasting tallit and kippah. For these two items, we obtained permission to enter our cantor’s vast wardrobe filled with religious garb.

“Use whatever you want,” she said with a smile. And we did.

At the time, Catherine’s hair had been more red than black, but with a combination of hair dye and photo editing, it turned out just the way we wanted. (When our own rabbi was once asked by a colleague if that was she in the cover photo, her response was simply, “No. My hair is straight. Hers is curly.”)

Catherine and I were very pleased when the first copies of the book were delivered to us. Our earliest book events were at Temple Sinai, Afikomen Judaica in Berkeley, and several local bookstores. Advance copies were sent all over the United States, and I made sure that the Oakland Public Library was amongst the first to receive them. We presented book talks at a number of synagogues in Northern California and received good press in both Jewish and secular publications.

In every normal way we geared up for volume two of the series. That’s when reality as well as the pandemic and personal health issues simultaneously reared their ugly heads and hit the fan.

As Rabbi Pearl Ross-Levy declared more than once in The Rabbi Finds Her Way, “God works in strange ways.”

I am unsure as to what the future shall bring. How about you?

As part of a special promotion tied to this essay and the upcoming holiday season, we are offering a free signed copy of The Rabbi Finds Her Way to readers who do not yet own the book. Please send an email or a message via Facebook or Instagram message to Robert Schoen. Include your mailing address (US addresses only), and as long as these promotional copies are available we’ll send one to you in early January. This offer ends 10 days after the publication of this post.

Our hope is that those of you who have already purchased our novel or receive a complimentary copy enjoy reading it and ask that you share your copy with family and friends.