Someone once explained to me the definition of the term professional musician. “It’s someone who gets paid for the gig.” That made sense to me. Ironically, these days getting paid to play is not as important to me as it used to be.

I’d say that my first public performance was when I sang “Jingle Bells” at my cousin Gil’s bar mitzvah. Gil is about eight years older than I am, so I would have been about five years old at the time. I remember being fascinated by the piano player in the band performing at the event following the ceremony. It would have been hard for him to ignore me. When he asked me if I would like to sing, “Jingle Bells” was just about the only song I could come up with. Sadly, I only knew the chorus—not the “Dashing through the snow” part. I remember my mother whisking me away after the song.

Coincidentally, my cousin Gil became an excellent jazz pianist as well as an aficionado, and still plays to this day. We’ve always had a wonderful time when we get together.

In the following seven decades, I’ve had many opportunities to perform as well as to experience the magic of music and musicians. In addition, I’ve often been fortunate to be in the right place at the right time.

I remember sitting in a restaurant in Las Vegas one time and saying to my dinner companion, “Isn’t that George Liberace over there?” Indeed it was! You might ask, How the hell did I know who George Liberace was? Well, my grandpa and I used to watch him play violin with his better-known brother, Lee, on black-and-white TV all the time when I was a little kid. Some things you don’t forget. (The other show Grandpa and I used to watch together was the Lawrence Welk Show. But I digress.)

When I was sixteen, my friend and high school classmate Mike Cahn informed me that he would be attending the Stan Kenton Stage Band camp at Indiana University for two weeks during the summer. Could I possibly go too? I asked myself. A few weeks later, following phone calls to the camp director and a check in the mail, I found myself on a plane to Bloomington, Indiana, with my friend Mike. In a stroke of luck, I wound up playing jazz guitar, my instrument at the time, in the number one student band (out of ten). Just to set things straight, however, I was not the best guitarist at the camp. In fact there were eleven guitarists, and I was playing second guitar in the first band. So now everyone knows.

It was an incredible two weeks. Every night we got to hear the Stan Kenton Big Band perform. Stan was a charming guy and an accommodating band leader. The campers all admired him and hung on every word. I can still remember some of his self-effacing anecdotes about his years on the road and his lack of piano skills compared to other players. In addition to the Kenton band, the Cannonball Adderley Quintet was also there. At the time his band featured Nat Adderley and Yusef Lateef. But best of all was the presence of clarinetist Buddy DeFranco, who at the time was performing in a duo with jazz accordionist Tommy Gumina. These were two very cool guys and wonderful musicians, and when we bumped into them at a local diner, they took the time to chat with us.

Buddy DeFranco & Tommy Gumina

Indiana University, still renowned for its music program, had an interesting music building. It was fabricated in-the-round, so you could walk around each floor, looking into the practice rooms and observing who was playing as you listened through the less-than-soundproof doors. I stopped dead in my tracks one day when I heard an unbelievable jazz pianist practicing and peeked through the small window in the door. It was none other than Don Grolnick. I knew who he was because he went to the same high school with my ex-wife. At sixteen years old, Don was already a phenom. He later played with the Brecker Brothers, Bette Midler, James Brown, and James Taylor, and was the featured pianist on one of Linda Ronstadt’s albums. Of course this fame came years after high school.

Don Grolnick

My roommate in the IU dormitory was a tenor sax player from Texas, the first person I ever met who was known by his initials, E.C. (he told me his first name under the pain of death if I ever repeated it). While walking through the town of Bloomington one afternoon, there was a young woman handing out samples of soft drinks on the sidewalk. While I asked for a Coke, my new friend E.C. asked for a Dr Pepper.

“What the hell is Dr Pepper?” I asked. They didn’t have Dr Pepper on Long Island when I was 16. E.C. was as surprised to find out I didn’t know what it was as I was to find out that it even existed. But I tried it, and fell in love. I drink it to this day.

One more celebrity musician I met at the Stan Kenton Camp was bassist and bandleader Chubby Jackson. He’d come up with the Woody Herman band and played with everyone from Louis Armstrong to Gerry Mulligan and Lionel Hampton. He also hosted a children’s TV show which featured a bass that had a face and could talk. Chubby was a real character and fun to be around. He gave me his card and invited me to visit him in his music studio in Hempstead, near where I lived.

Chubby Jackson

A few weeks after returning home, I asked my 19 year-old friend and neighbor Neal Weiss if he’d drive me to see Chubby, and he enthusiastically agreed. Neal was a pianist from the Jerry Lee Lewis school of playing, and my mother often complained about the blood stains on the keys after he’d play our piano.

We drove out to Hempstead and when we arrived Chubby was chatting with a tall blonde woman of a certain age who flashed us a charming smile when we were introduced. I didn’t recognize her name, but Neal’s eyes opened wide. Chubby asked us to wait a few minutes until he finished his conversation and we went to the other side of the room.

Neal, who’d been taking a class in the history of jazz at Hofstra College, whispered to me, “I know who she is! She’s in my textbook.” She was pianist Marian McPartland, who later became very well-known from her popular program “Piano Jazz,” which ran on NPR from 1978 to 2011.

Chubby, Neal, and I chatted for a while, and it was a pleasure to see him. Several years later I met McPartland again when she was playing at a New York City bistro. When our eyes met, she flashed me that same brilliant smile.

Still in high school, at age 16, I was playing guitar in a rock band with a few of my friends. We called ourselves the Blue Velvets, and we thought we sounded much better than we did. We had cool business cards my Dad designed, and played dance gigs around Nassau County.

One Saturday we traveled to some high school gym for a “battle of the bands” and played as well as we could. As I was putting away my guitar, I couldn’t help but hear the lead guitarist of another band that was currently playing. He was, simply, fantastic.

I went over to listen. He was a chubby kid about my age, and was as good a guitarist as anyone I’d ever seen or heard. I approached him after he finished playing and we exchanged business cards. (Everyone had to have a business card in those days, indicating that you were a professional musician, even if you were only 15 or 16.)

I called him a few weeks later to play a gig with me. I remember three things from that night. First, he was late for the gig. Second, I paid him $15. Third, he played circles around me.

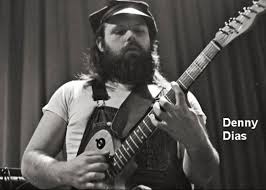

Years later when I was a grad student at Berkeley, I was looking through a stack of LPs at a Telegraph Avenue music store and stopped in my tracks when I came across a picture of that same chubby guitar player on one of the album covers. He was wearing bib overalls and had a bushy beard. It was the same Denny Dias I knew from that high school gym and, I discovered, a founding member of Steely Dan, one of the best rock bands of all time.

As a freshman at Boston University in the mid-1960s, I was able to see several well-known musical groups, including the original Dave Brubeck Quartet with Paul Desmond. They played Take Five, of course, but it no longer sounded anything like it did on the record. I found this to be the case with other well-known jazz groups whose recordings were “hits,” but they continued to evolve through the years.

Later the same year I went to hear the George Shearing Quartet. I owned several of Shearing’s LPs. As a jazz guitar lover, I paid particular attention to the band’s current guitarist, someone I’d never heard of. During the intermission, I snuck into the area being used as Shearing’s dressing room and, holding one of his LPs in my hand, asked if I could get George’s autograph. The guy at the door grudgingly led me to where Shearing was sitting and I got my autograph. Unlike Stan Kenton, George Shearing was not charming. He was also blind, which made the autograph process a little awkward—for him, not for me.

After the performance was over, I walked over to the guitarist who was packing up his instrument. He was a bald guy with a mustache and he looked up as I approached him. When I told him I played guitar, he smiled, shook my hand, and was simply sweet and friendly. I asked his name, but didn’t get it the first time, so I asked again. It was Joe Pass, who became one of the most esteemed jazz guitarists of the Twentieth Century. Who’d have guessed?

Joe Pass

About fifteen years later, I went to see him at the King of France Tavern in Annapolis, Maryland, where he was performing solo—just him on the jazz guitar.

Near the end of the first set, he looked at the audience and asked, “Is there anything anybody wants me to play?”

One guy called out a song title and Joe said, “Nah, I don’t want to play that.” The crowd laughed.

Without thinking much about it, I called out, “How about All The Things You Are?”

He nodded and said, “Absolutely. Great song!” and proceeded to play it unaccompanied, sounding like three guitars instead of one.

On my way back from the men’s room during intermission, I spied Joe sitting with two other men at a corner table. He was smoking a cigar.

I approached them, and when he looked up I said, “I wanted to thank you for playing my request.” He acknowledged that with a smile, but I continued.

“Joe, I met you once before when you played at Boston University with the Shearing Quintet.”

He groaned through a smile. “Oh my God, that was so many years ago!”

I went on. “I was 18 at the time and I didn’t know a damn thing about anything. But I did know that you were fantastic, and I went up after the show while you were putting your guitar away to let you know how much I enjoyed your playing. And now I also want to tell you that you were very kind to me. You treated me with respect.”

I could see a special look come across his face as I added, “And you weren’t a jerk.”

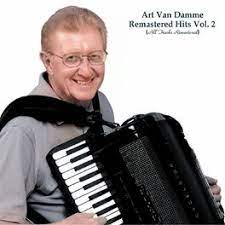

He shook his head, stood up, and offered his hand, saying, “Let me introduce you to my friends.” The guy on his left was somebody I didn’t know, and I’ve forgotten his name. And then Joe said, “And this is my good friend, Art Van Damme.”

I was stunned and took a step back. “Holy Shit! Art Van Damme? Are you serious?”

Art smiled a bit as he said, “You’ve heard of me?”

I replied, “Are you kidding? The most famous jazz accordionist in the world?”

By this time Joe Pass was laughing so hard he almost fell off his chair. He said to Art, “I told you somebody’s heard of you!”

I’d obviously made both of their days.

At the same venue a year or two later, I accosted veteran jazz guitarist Barney Kessel.

As he was walking into the lounge, I blocked his path and said, “Barney, I’ve been a fan of yours since I was 12 years old. I’ve tried to get to meet you a couple times before, but they would never let me through the gate at the concert. Is there a chance we could chat for a few minutes after the show?”

He sighed and said, “Sure. Meet me at the bar at intermission while I have dinner.”

Although not a household name, Barney Kessel was a member of many prominent jazz groups as well as a “first-call” guitarist for studio, film, and television recording sessions. He was an early member of the session musicians informally known as the Wrecking Crew. Years before he’d appeared in the short film “Jammin’ the Blues” where (I later read) as the only white musician in the group, and in an effort to avoid controversy, they’d put dark makeup on his hands as they filmed a close-up of his finger-work while playing. In addition, he was the guitarist on Cry me a River, Julie London’s 1955 hit record. (I own the LP and have had a crush on Julie London from the moment I bought it.)

Barney Kessel

After his first set, I met Barney at the bar where he was eating a steak and drinking white wine. I remember that we talked about music for about three or four minutes during which time he taught me a musical lesson that I never forgot and keep in mind to this day when I accompany jazz vocalist Catherine deCuir on the piano: “When she’s singing, you don’t play much. When she stops singing, then you play what you want.” If it worked for Barney Kessel and Julie London, I figured it would work for me; and I believe it does.

For the remainder of the fifteen minutes I sat with Barney Kessel we talked about divorces, our ex-wives, and how he was constantly being served subpoenas when he landed at any airport in the country.

Obviously, being a jazz musician is not all sunshine and lollipops.