Being a musician (or any type of artist, I suppose) adds a special burden to one’s life. It certainly has to mine.

An example of this dilemma was well-illustrated in an old Cathy cartoon I once read. As I remember it (I’m paraphrasing), she is interviewing a client, who says, “I’m not really a client—I’m actually an actor.” To which she responds, “I’m not really a consultant—I’m a ballerina.” This is followed by several panels where people walking by reveal their “inner selves”—the side no one usually sees.

Thus when the question was put to me for over 37 years, “So, what do you do?” I always said, “I’m an optometrist—but I’m really a jazz musician,” although the last half of that response was only uttered in my mind.

In his 1976 movie The Front, Woody Allen is doing a blacklisted friend a favor by impersonating a writer. At a large social gathering he’s attempting to flirt with a woman who says, “You’re kinda cute. What do you do?”

“I’m a writer, “ he says enthusiastically, at which point she turns on her heel and walks away. Another attempt with a second attractive woman ends in a similar manner.

When a third woman he approaches asks him what he does, he responds, “I’m a dentist.” She reacts with something akin to, “Ooh!”

He adds, “But I have a problem.” She pauses, unsure of what to expect. He continues, “My office is just too busy. I may have to hire more help.” She swoons.

To me, Woody is making a point not only about “what women want,” but about how we view ourselves, our occupations, and how we present ourselves to the world through our work.

Certainly there are women who are attracted to jazz musicians. God only knows why—word on the street is that we’re all junkies. Or always broke. Or both. You certainly wouldn’t want to bring one home to meet your parents.

Perhaps it’s within that framework that I became an optometrist.

Was there ever a kid in kindergarten who, when asked “What do you want to be when you grow up?” responded, “I want to be a jazz musician.” (For that matter, how many kindergarten kids desire a career in optometry? I’ve only met one.)

There was always music in my house. My mother played the piano well, mostly show tunes from sheet music piled in drawers and cabinets. My father often sang along with her; he had a pleasant tenor voice, although I didn’t know at the time what a tenor was.

Piano lessons started for me when I was six or seven. But even before that, while exploring the hallway coat closet, I discovered a Silvertone guitar in a canvas case. It was too big for me. Fortunately, I also found a small ukulele.

I learned to play the uke from an old orange-covered method book I found in a living room drawer. Some of the songs included in the collection dated back to the minstrel era. (You just don’t hear “Old Black Joe” anymore, for obvious reasons.) That said, I learned a lot of chords and was able to play along with my Mom when she opened the sheet music to songs by Cole Porter and Rodgers & Hart.

I grew up in a traditional Jewish home. Now, you may find this surprising, but the ukulele is not generally considered a Jewish instrument. (What did I know?) In fact, I learned my chords well enough that when the cantor in our synagogue, Charles Davidson, announced that he was forming a temple “orchestra,” I joined as the featured ukulele instrumentalist. I must have been eight or nine.

Only now do I realize how brave Cantor Davidson must have been. (My mother was, at one time, president of the Temple Sisterhood, which was as lofty an office that women could achieve in those days. Maybe the cantor did not want to mess with her.) He later moved to a larger congregation and became a well-known educator, composer, and arranger of contemporary Jewish music. There are many clergy I’ve met who have been impressed (and surprised) to find he was a member of the team officiating at my bar mitzvah (an event that does not appear on his resume).

My career as a child ukulele player was brief, although I’ve been known to play the instrument on cruise ships to Hawaii. (It’s like riding a bike.)

Through the years I learned to play the piano, but really aspired to be a jazz guitarist, receiving my first Gibson electric at the age of 12. In fact, a year later, I sat in with the band at my bar mitzvah reception (I can’t recall the cantor being there).

As a teenager, my heroes included legendary guitarists Barney Kessel and Joe Pass, both of whom I was honored to meet decades later. I listened to my jazz LPs repeatedly. Somehow the grooves did not wear out.

When I was about 14, a kid from my high school named Marc called and asked if he could bring his guitar over. Not only was he a few years older than I, he was also tall and rather imposing. He showed up with a beautiful white Fender Telecaster and we plugged into the amp in the rec room in our finished basement.

I learned an important lesson that night. A 14-year-old can be a better player than a 16-year-old, no matter how tall the older kid is.

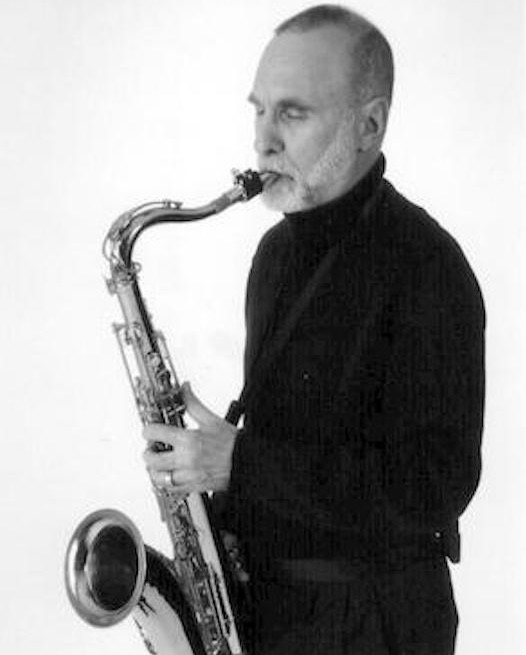

I suppose this is the way it is with many activities—sports, dancing, academics. Perhaps it’s part of the maturation process. As a musician, you spend your whole life trying to perform with others who are at least as good as you are and hopefully better, and you hope that they’re willing to play with you. I’ve had the experience of trying to sit in with monster players who obviously were not interested in me being there. Even if you’re a decent player on one instrument, if you switch to another, as I did in my forties when I took up the tenor saxophone, you run up against the same discriminatory behavior. Sometimes it’s a bitter pill to swallow.

Through my teenage years, I played guitar in several different bands. Often I was the band leader, a role I took to naturally for some reason. A band leader generally chooses the tunes, maps out some kind of arrangement, and gets the gigs. When I was 15 or 16 a “good” gig meant $60 split four ways—that’s worth about $130 each today. (These days, 60 years later, I often perform with a vocalist as a duo and we’ll split 60 or a hundred bucks two ways. Musicians don’t know about inflation, I suppose.)

One time I took part in a “Battle of the Bands” at some Long Island high school. I was observing another group performing and was totally awed by the kid playing guitar. He was my age, although shorter and a bit chubby. But he was just phenomenal. I approached him later and we exchanged business cards (you had to have a card), and asked him if he’d like to play with me on a little gig I had coming up at some kind of Rotary or Lions Club party. “Sure,” he said. We played the gig, he made twenty bucks, and I never saw him again. I did, however, recognize his name years later when I saw his picture on an album cover. Turns out he was Denny Dias, one of the founding members of Steely Dan. Definitely a monster player.

One of the paramount necessities of a band in the 1960s was to have matching outfits. I still have the shirt that my band, The Sultans, wore. Another band I was in, The Blue Velvets, required blue blazers, white pants, and skinny black ties. Then there were The Manhattans, who wore houndstooth Nehru jackets.

Years later, I learned the one thing you never say to guys in the band: “Just wear a jacket and tie to the gig.” At one wedding I performed at, the piano player showed up in a plaid jacket, yellow dress shirt, striped tie, and (as I recall it) green pants. He was an excellent player, but an adventurous dresser, and I learned an important lesson. From then on it was either “dress black” (black pants, black shirt, black shoes), or black tux. This didn’t always solve the problem. One of my favorite guitar players once showed up to a wedding gig smartly dressed in his black tux, black shoes, and white socks.

At some point I recognized that there are three types of musician. The first consists of those who are solely dependent on music income. They perform, compose, arrange, and often teach. Period. The second type includes people who refer to themselves as musicians but make their living from casual employment such as restaurant work, the building trades, retail sales, and so on. Often they are very good musicians, but the bulk of their income comes from bussing tables or building decks. There is nothing wrong with this; in their hearts, they are musicians or performers, often waiting for a big break.

The third group includes doctors, dentists, lawyers, CPAs, and others who have spent many years in higher education. This is the group into which I fall, and in some ways, it’s the toughest to maintain. I know one excellent sax player who’s a CPA and disappears during the tax season. Another guy I know is a university professor and worships the late pianist Bill Evans. One trombonist I know is an OB-GYN. The host of a jam session I’ve attended for decades is a pediatrician and mohel, and loves to sing.

I recall one of those jam sessions years ago where I bumped into a guy who told me he’d always wanted to play the saxophone, but he was just too busy at work.

“In fact, I just got off the phone with a client,” he said. It was a Sunday afternoon.

“What do you do?” I asked.

“I’m an attorney.”

“Sounds to me like you have a conflict between the saxophone and billable hours.”

He didn’t argue with that assessment. I do know one attorney who’s a good sax player. Somehow he figured out what was really important to him.

So while you occasionally hear of a professional musician who is or was a surgeon or a psychiatrist, and has had a successful recording or performance career, traditionally jazz musicians have been drug users as opposed to drug prescribers.

For myself, it’s difficult for me to regret the professional and musical choices I’ve made. I sat in with the band at my senior prom, and again at my wedding—the first one. At my second wedding, my own band played, and many of my musician guests sat in with the band.

In my 50s and 60s I was a professional wedding and event band leader, and often made 3 to 4 times as much for a 4-hour gig playing the sax or keyboard as I did working 7 or 8 hours in my optometric office. To this day I can put on my tuxedo faster than you can put on your makeup (if you wear it).

I’ve written and collaborated in musical theatre and composed liturgical choral works. I’ve also written and arranged concert music for middle school, high school, college, and military bands.

One thing I learned long ago:

Some things you do for money, and some things you do for love.

For me, making $15 when I was 16 felt just as good as making $1,000 when I was 60. In the end, some gigs are better than others. And you don’t always know that when you start playing.

When I finally had a chance to sit down with legendary jazz guitarist Barney Kessel (he was eating a steak and drinking white wine), we talked about music for about five minutes. The rest of our conversation was about our ex-wives.

I met Joe Pass twice, once in 1965 before he was a headliner, and years later when he was. I told him about our first meeting when he was the guitarist in the George Shearing Quintet, and remarked at how he had treated me after the show—with courtesy, kindness, and respect.

“You weren’t a jerk,” I told him. He laughed, and I thanked him again. He seemed more touched by my comments than anything I could have said about what a great player he was. We’re all just people looking for a little love.

I’ve been retired from optometry for a number of years, but I’m still a jazz musician. One truth remains constant. There will always be players who are better (or taller) than you, and others who are not. I recognize that and accept it. Maybe the better players put in their 10,000 hours and I didn’t.

Regardless, I take music seriously. At 66 I took up the flute as a “retirement project.” In my early 70s I moved to the trombone—unlike any musical thing I’d ever done before. As some point I realized that even practicing an hour a day I’ll never accumulate 10,000 hours on the horn. For better or worse, I’m reconciled to not becoming a master of the trombone. That does not mean that the effort (aka “work”) I put into it every day is not worth it.

When people say to me that playing an instrument must be a lot of “fun,” I look at them like they’re crazy.

Occasionally I wonder, if I was in Woody Allen’s shoes in the movie and the woman asked me what I do, would I tell her I was an optometrist? And would she swoon? Or, what if I told her I was a jazz musician and she didn’t swoon. Would I even care?

I’ll have to think about that.