A year or so ago I had a strange dream. Of course, most dreams are strange. But this one was both beautiful and, perhaps, telling:

A young man is standing with a young woman on the deck of a ship. They are looking at the vast night sky above them. He says to her, “When I look at the sky on a night like this, I am amazed at all of the shooting stars.”

She responds, confidently, “Those stars are sending money. You just have to know where to look for it.”

The dream woke me, and I spent a long time thinking about it. It reminded me that sometimes money does come to us out of the blue. It is a special gift, particularly when you need it. But, as I’ve learned, it can be even more problematic if it comes when you don’t need it.

I remember the first time I saw a beggar—at least that’s what they used to call them in those days. I was a small boy walking with my father in the New York City subway system. It was 1952 or ’53, and as I held his hand on the way to his office where I would spend the day, we walked by many men sitting on the subway platform. Most were dressed in what I can only describe as rags. A fair number of them were amputees, most likely World War 2 veterans. Although they all looked old and haggard, I doubt that any of them were much older than my father, who was also a war veteran. Yet here he was, dressed in a suit, tie, and hat, appropriate for his white-collar office job. The smell of the subway—strongly reeking of urine—was something I can remember even now almost 70 years later.

The men, sitting or lying on the concrete, asked passersby if they could spare a dime. Some actually held tin cups and shook them, the coins rattling within. It was not until decades later that I would hear the Great Depression song written by Yip Harburg and Jay Gorney, “Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?” Yet when I did hear that song for the first time, it was those amputee veterans and the smell of urine that immediately came to mind.

As any child might, I asked my father about these men. His actual response is long forgotten, but since I did not see him drop any coins in their tin cups I can only imagine that he was not particularly empathetic to their situation. Over time I became more aware of his attitude toward people who did not (or could not) “recover” from the war as he and most other veterans did. In fact, he rarely if ever mentioned his time in the service until he was in his 60s or 70s, and by then his memories were for the most part vague or nostalgic.

When I moved from New York to San Francisco in 1969, the time period was called The Summer of Love. It might also have been called The Summer of “Spare Change?” The stereotypical long-haired hippie was becoming a familiar fixture on street corners in the city. Many passersby did not take them seriously. Others might reach into their pocket for whatever change they had. Me? I was confused. Jobs were available, college was cheap, and most of these people were, like me, in the prime of their lives. I, like my father, was not really sympathetic to their requests for money. The day after I arrived in San Francisco, I started looking for a job and found one in a week or two.

From 1971 to 1976 we were living in the East Bay and I was back in school. The city of Berkeley (particularly Telegraph Avenue) had an abundance of spare-changers, but as a student I did not feel obligated to donate to their lifestyles. I had my own problems.

After graduation in 1976 I moved to Maryland, where the “spare change culture” seemed to be lacking. It was an intense time for me, full of turning points and learning experiences.

Seven years later I returned to Oakland, and was now a working professional. The office in which I worked was located on Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley, a main thoroughfare just a few blocks from the University itself. On every street corner, it seemed, was a young man or woman asking for spare change. They were part of the landscape. Some would play the guitar, their open instrument case littered with nickels, quarters, and a maybe a few dollar bills.

One of the mantras of my own life goes like this: “Everyone’s a critic” (I’ve threatened to have that etched on my gravestone). And as critics go, I am among the worst.

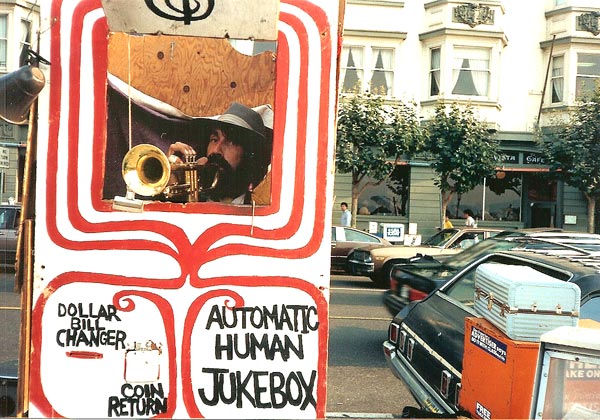

When I would pass a street musician, I might throw in a buck if the performer was particularly good, or entertaining. There was one guy who would sit in a large cardboard box. If you put some money into a slot in the box, this little curtain would go up, and the guy would perform a song on his trumpet; when he finished, the curtain would drop. A little ingenuity worked wonders, and he always seemed to gather a small crowd.

On the Berkeley block where I worked, there was a woman named Carolyn. She sat on a plastic milk carton on the corner near the Wells Fargo Bank. She’d arrive before 10 am and was still there when I went home at 6 pm. She was obviously a hard worker—well, at least she put in the hours. I’d see her when I went to lunch or to the bank. And all day long she would chant the same two words in a sing-song melody: Spare change? I can still hear her droning, plaintive voice. I didn’t like it then, and I still don’t.

Carolyn’s presence was accepted and/or tolerated for many years, and along with the BART station and the bank she was part of the landscape.

Then one day, she wasn’t there. And she wasn’t there the next day, or the following day. I couldn’t help wondering what happened to her. I didn’t like her, but for some strange reason I was aware of something missing. She’d become part of the feng shui.

A few weeks later a Berkeley cop came into my office for an eye exam and I asked him if he knew what had happened to Carolyn. He chuckled. It turns out she’d been arrested by the Berkeley Police for selling hard drugs to Berkeley High School students.

“We’ve been watching her for a year,” the officer told me. “But she was very clever.”

More clever than he knew. A few weeks later, there she was, back on the street. I didn’t realize it at first, because part of her punishment by the overly-liberal Berkeley legal system was that she could no longer panhandle on the same corner. So she’d moved two blocks over to an area where I seldom walked. Thus she was now comfortably out of sight and out of mind (my sight, and my mind, anyway). I don’t know if she resumed selling drugs.

Yet here I am thinking about her again. What happened to her? Is she (like myself) collecting social security benefits every month? Did she contribute to an IRA? Was she able to pay off her mortgage?

The question of whether and how much to give to charity is one each person has to answer individually. I do not come from a background where tithing is a normal phenomenon (although my parents were always members of the synagogue). I’ve always been fascinated by the concept that people will give a sizable percentage of their income to a church or charity regardless of their own situation. I’ve had friends who indeed gave “till it hurts,” and in spite of the pain they inflicted on themselves and their family they seemed content to do so. I also have friends of financial means whose giving is minimal. The question of what is “enough” is a personal and difficult decision; perhaps even a struggle.

I have a one friend who is active in philanthropy. During a recent walk I asked him to explain to me the difference between charity and philanthropy. As I recall, his answer had more to do with magnitude than anything else. There have been some stories in the news these days about the wealthiest people in the world and the levels (and recipients) of their philanthropic giving. I am fascinated by these stories.

The congregation to which I belong has for many years been active in collecting food donations and working with the Alameda County Community Food Bank to distribute it. In pre-pandemic years our congregation would try to outdo its previous years’ giving, announcing the numbers of tons of food collected. These efforts were severely impacted by the pandemic and the cessation of in-person religious services. Giving did not stop altogether, but I do know that food banks and similar organizations took a big hit. This was particularly devastating because more people than ever were in need.

Because I am retired and do not have a job, I was the beneficiary of the government’s stimulus payments. After receiving the first unsolicited payment, I wondered, “What the hell’s going on here?” I was not in need and I was not suffering.

The more I thought about it, the more I felt that it was my job to “redistribute” these funds.

My first response was to increase the modest monthly gifts I’d already been giving to two organizations—one local, the other national—that distributed food. The charities to which I donated were each generous in their gratitude, but I felt something was missing. These gifts were, after all, just another line item on my credit card statement. The personal element of “giving” was just plain missing. I was stumped.

Then, a few nights later, I saw a shooting star!

Not really. But here’s what really did happen:

I was walking to the library to return a book, and on the way I passed a shabbily dressed old man digging through a trash bin. He was really old. Probably about my age. When he turned toward me I could see that most of his teeth were missing.

“Hey, brother, can you spare any change?” he rasped.

I ignored him and kept walking. After dropping my book off at the library, I decided that I deserved a donut. Did you ever have that feeling where you deserve a donut? Well, that’s what I felt, probably because I could see the donut shop from where I was standing.

So I walked over to the donut place, and when I was about 10 feet from the entrance I spied a twenty-dollar bill on the sidewalk. My first thought was that the twenty was surely glued to the sidewalk and that there was a camera filming this whole scene. I would certainly look like a fool as the video of me trying to scrape the bill off the sidewalk immediately went viral on Tik-Tok, Facebook, and Candid Camera. This fear did not stop me from walking over and scooping up the twenty, shoving it into my pocket as I entered the donut shop.

I ordered my donut at the counter and paid with the twenty. I stuck the change (including a few fives) into my pocket. As I walked home, eating my chocolate and coconut-covered donut, I heard a voice inside my head.

“It’s not yours,” the voice declared. “The twenty was a gift. So was the donut.”

And that’s when I hunted down the shabbily dressed really old guy (my age) with no teeth and walked up to him with a five-dollar bill in my hand.

“Here you go, brother.”

He took the money with surprise, smiled (no teeth), and not unexpectedly, said to me,” God bless you, my friend.” I’ve had people say “God bless you” to me before, and it aways feels good.

I took a round-about route back to my apartment and managed, without much difficulty, to give away what was left of the twenty. I was pleased, but it wasn’t enough.

The next day I went to the credit union and withdrew the amount of my stimulus check—in fives. I started giving away fives to anyone who would ask and many who didn’t. There are still a lot of fives left, and more where those came from.

I can tell you this: no one turns down a five-dollar bill. Virtually every recipient is grateful, whether they asked for the money or not. Occasionally I get a “God bless you.” There’s always the hope that the recipient doesn’t blow my small gift on cigarettes, alcohol, or drugs; but that’s outside of my control.

Growing up, I recall hearing many times that it’s better to give than to receive—it’s from the New Testament, Acts 20:35, so I’m not sure where exactly I heard it. (I also learned first-hand on my walk across America the importance of being able to receive as well as to give.)

Regardless, I can assure you this latest experience in giving feels damned good.