The death of my father on March 7 (as well as that of my mother in 2012) helped me learn the true meaning of the word community.

I truly appreciate the outpouring of caring and kind words from friends, most of whom never met my father but understand (generally first-hand) what it is like to lose a parent or other close relative.

My father was 96 when he died. For the last few years of his life he suffered from both blindness and Alzheimer’s—a terrible combination.

Dad took his own sweet time making a very slow exit. I sometimes felt that he was hoping to achieve notoriety by being either the oldest man alive, or at least the last living veteran of World War 2. Sadly, or perhaps fortunately, this was not meant to be.

My wife Sharon and I, my sister Eve and her husband Russ, and our children, were along for the ride, enduring the sadness and frustration of loving a parent or grandparent who does not recognize you or remember who you are, but who still appreciates the closeness of someone holding his hand, talking to him, reminding him of people and experiences he no longer recalls, and singing songs that occasionally bring back a flicker of recognition.

Ironically, although I only visited my father every 4-6 weeks, I was in Southern California to see him on Monday, March 6. After his caregiver got him out of bed and completed the morning bathroom ritual, we set dad up in his wheelchair by the kitchen sink and I gave him a haircut—the same buzz cut I give myself—and then I spent the next 45 minutes or so singing to him.

It’s no coincidence that because I perform for memory care residents as part of my job as a musician that I had on my iPhone a list of the songs in our repertoire, which included old-time titles like, “Ain’t She Sweet,” “Bicycle Built for Two,” “Side by Side,” and “Me and My Shadow.” I was fortunate in remembering to video a few of these on my phone. At one point as I sang, my father reached out his hand and his caregiver, Delia, took it and “danced” with him. He was definitely enjoying himself. I thought about this on the flight home, and showed Sharon the video of Dad smiling slightly as he stared into the distance, listening to the words, “Oh, we ain’t got a barrel of money…” and “dancing.” I was pleased. It was a pretty good visit.

The next morning at 7 am I received the phone call from the caregiver informing me that my father had just passed away. I like to think that he died “peacefully,” but I don’t really know. Let’s just say he did, and leave it at that. My sister was present a few hours later when Dad was taken out for his last drive in a car.

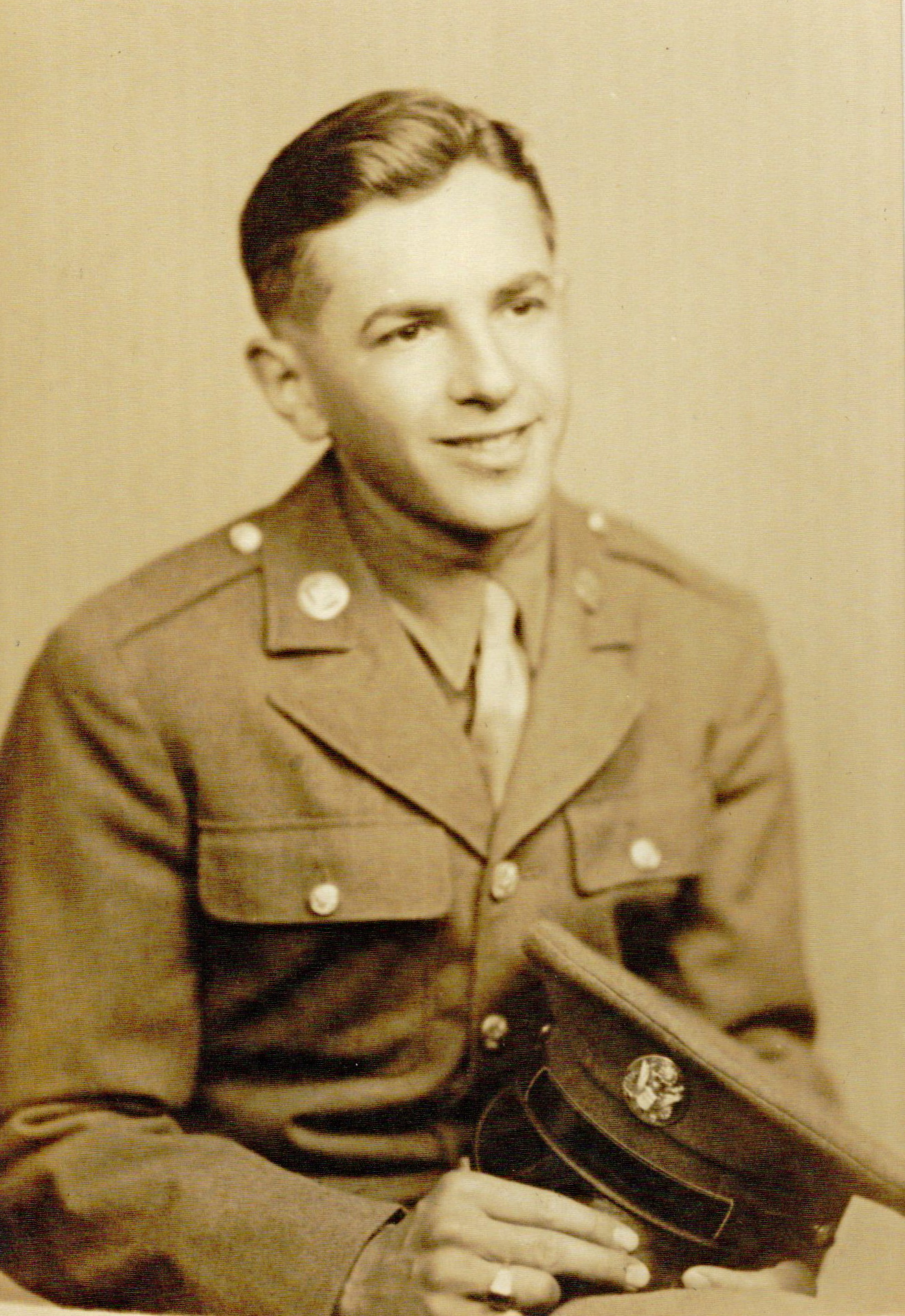

My father, Michael W. Schoen, was a talented man, both charming and handsome. Dad was a fine artist, working in both oils and water colors, and a successful businessman, running his own advertising agency for many years, until he just couldn’t anymore.

His name at birth was Meyer Schoenfeld. As was the fashion in those days, when he started his own ad agency he shortened his last name “for business purposes” to Schoen. As long as he was going through the process, he officially changed his first name to Michael, and added the middle initial W. For those who might wonder, the “W” did not stand for anything—he just liked the way it sounded. He was that kind of a guy.

Along with my mother, Pearl, he was one of the founding members of the Wantagh Jewish Center, a conservative congregation, which met for the first few years of its existence in the Wantagh Fire Station.

He was a member of the temple Men’s Club and played on their softball team. He painted posters for the temple’s shows and fundraisers. When the temple was putting on the Broadway musical, “Guys and Dolls,” my dad tried out for the role of Sky Masterson, the romantic lead. That was the only role he wanted, and when he didn’t get it, he declined to participate in the show. I didn’t understand it then, but I did later as I learned more about his personality.

My father graduated from John Adams High School and was active in art study and projects throughout high school, winning awards and working as a professional in the commercial art field even as a teenager. He later attended Pratt Institute, which has become one of the premier art schools in the country.

In 1942 we were at war, and he entered the Army Air Force, wanting to be a pilot. Everyone wanted to be a pilot. But he instead became the flight engineer and top turret gunner on a B-24 bomber. His crew was based in the Philippines, and flew 44 bombing missions over the South Pacific. Unlike many others, he and his crew survived.

One story he told was of a panicked call on the intercom from the pilot that there was an oil leak and a fire in one of the engines. As the flight engineer, Dad needed to know the detailed workings of the plane. Calmly, amidst the noise and yelling of the other crew members, he walked up to a particular valve, shut it, and the leak and fire were contained. Then he unceremoniously returned to his top turret and gun. He was unflappable like this in later life, too.

As a boy, I’d sometimes see other dads on the street changing the oil in their cars. I once asked him why he didn’t change the oil in our Buick. He laughed and said, “Bobby, I could change the oil in a B-24 bomber, so I certainly could change the oil in my car. But why get dirty? I work hard at my office so I can afford to pay other people to change my oil.” This was a personal philosophy that I learned to take to heart myself. (Although I don’t think I could change the oil in a B-24.)

That “job in his office” was Monday through Friday. He left the house each morning at 7:00, took the Long Island Railroad and then the subway to Manhattan, and came home at about 7:20 each night. He wore a top coat and a hat, just like in the movies and on TV. He played bridge with the guys on the train, two men facing two others, with an unfolded New York Times on their knees serving as a card table. My father, as I saw during my boyhood “trips to the office,” was generally the score keeper, and he could snap trump cards on the Times with as much enthusiasm as anyone else. He was an excellent card player. Sadly I did not inherit this trait.

He could be stubborn, though. One time Sharon and I were taking our sons to Hawaii, and we asked my parents if they’d like to share the condo in Honolulu with us. My mother came, but my father said “No, I’m not interested in going to Hawaii. I’ve already been there.”

“Dad, you weren’t in Hawaii—you were on an airstrip on some island during the War!” He wouldn’t budge, and we went without him.

At one point when my parents were still in good health and were visiting me and Sharon in Oakland, he began talking about his bomber crew.

“Dad, do you keep in touch with any of the other crew members?”

He laughed. “No, I’m sure they’re all gone.” He was in his seventies at the time.

“Wait. So, you’re telling me that you’re the last man standing?”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, you think they’re all dead and you’re the only one left alive?”

“I guess. I don’t know.”

I gave him a pen and a piece of paper and asked him to write down the names of the ten men in the crew. I could see him visualizing the positions in the plane as he wrote the names—pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier, radio man, etc. He gave me the completed list, which included several Italian- and Polish-sounding names. I went to the internet, and it took me five minutes to find the first guy and his telephone number.

“Here, Dad. Call him.” I handed him the phone, and listened to one side of the conversation.

“Hello? Is this Gus? Gus, you’ll never guess who this is!” And so went the game. Dad told me later that Gus started to cry when he realized my dad was still alive. In the end, six crew members found each other, and with their wives had a reunion in, I believe, Cincinnati, near where one veteran lived, and near where my son Adam lives. There was one more reunion, but that was the last one. The men were failing physically, one had major surgery, someone else’s wife died, and the crew finally broke up. I found photos from one of the reunions—old, overweight, and physically challenged men, who once lived together in a tent at an air base, flew in a thin-metal-shelled, four-engine monster, and dropped bombs on the Japanese enemy. Indeed, for my parents and their generation the Japanese remained the enemy long after the two countries became allies.

He was a good father, a mentor, and a role model. He was honest in business and in life. Like the stereotype good husband, he generally did what my mother asked or told him to do, saying, “Yes, Dear,” when it was called for.

One thing Mom hated, for some reason, was to hear my father whistle. I don’t know why—he was a really good whistler! I remember sitting watching TV with my father one night when I was maybe ten or eleven. We were watching a show called “Tombstone Territory.” Each episode opened with a guy whistling the melody of the theme song. After a few seconds of this, my mother shouted from the kitchen, “Michael! Stop whistling!” My Dad and I shared a very private laugh that I still remember well.

My dad was very mechanically inclined, and like a lot of other suburbanites, finished the basement in his Long Island home, kept the house painted, groomed the lawn, and even dug a well to provide water for his two walnut trees and a fig tree that never did bear figs that I can remember.

Years later, I asked my mother what she thought he might like for his birthday. She said he was talking about a new shower head. I told her I’d get one for him. At the time, I was living in California and we were having a terrible drought. Everyone was trying to save water—people weren’t flushing their toilets; they were taking showers together; everyone’s lawn was dead. I bought Dad a top-of-the-line Teledyne shower head that had a water saving device built in to restrict the flow, and sent it to him.

On his birthday, I called and asked him how he liked it.

“It’s terrific! Thank you very much.”

“It’s working well?”

“Well, not at the beginning. It seems something was preventing the water from coming out. So I opened it up and sure enough, there was this little metal ball that was restricting the flow. I took it out, and now it works great!”

When I was in college, my parents decided to build a vacation home in Woodstock, NY. They would drive up every week and watch the progress of the construction. The house was eventually finished and furnished, and they joined the Woodstock Golf and Country Club. They loved going up there.

Years later I heard the story about a wealthy businessman who was visiting the resort with the thought of buying it as an investment. Dad loved to paint, and he was a wonderful artist. He had painted a picture of several golfers putting at a particular hole on the course that featured panoramic views of the Woodstock countryside, and it was on display at the clubhouse. At a reception that night, my father glanced over to see the flamboyant businessman standing in front of the painting, obviously admiring it. Dad walked over to him and asked, “Do you like that painting?” The guy nodded, “Yeah, I do. It’s one of my favorite holes here at the club.”

“I painted that picture.”

“You?”

“Yes. That’s my signature in the bottom corner there.”

“I’d really like to have this picture,” the guy said.

“Sure. It’s available,” my father replied. “How much are you willing to pay me for it?”

“Pay you? I wouldn’t pay you anything! But you could give it to me as a gift.” When he saw my father wasn’t interested in giving him the painting as a gift, he turned and walked away.

When I asked my father about the incident, he merely said that the guy was a jerk. That jerk is currently the president of the United States.

My sister tells me the painting now hangs in my brother-in-law’s office.

I’ve heard from many women who knew or met him that my father was not only handsome, but that in his own quiet way he was charming. I saw this in action a few years ago after my mother had died. Dad’s vision was really bad by this point, and he was always complaining, “Why is it so dark in here? Why don’t they turn on some lights?” Not only was he going blind, but he was already starting to show signs of dementia. It got to a point where I’d say to him, “Dad, we’re going inside now, and you’re going to say to me, ‘Why is it so dark in here? Can’t they turn on the lights?’”

One day we slowly walked into the bank so he could deposit a check, and I heard the inevitable, “Why is it so dark in here—I can’t see anything!” As we approached the teller’s window, he looked up at the middle-aged blonde Persian woman behind the thick glass screen and says to her, “If I knew I was going to have such a pretty lady taking my deposit today, I would have brought more money!” She laughed and said something back, and I realized there was some serious flirting going on. I couldn’t believe it. I love to think about that scene. The problem is that he forgot about it all very quickly, as he did pretty much everything.

It was a this point that I became his working memory. I wrote a synopsis of his life, put it in a plastic sleeve, and read it to him each time I visited him. I’d ask, “Dad, would you like me to tell you about your life?”

“Sure, why not?”

Occasionally there was a glimmer of recognition at some of the items or people I’d mention, but as the next couple of years went by, there was no recognition at all. Except for one thing—when I said to him, “Dad, do you remember your niece Claire?” he’d reply indignantly, “Of course I do!”

Claire was his niece but was only a few years younger than he. My father’s parents owned a large dry goods store in the East New York section of Brooklyn, and Claire has told me that Dad and she would play games in the store when she was 4 or 5, dancing up the aisle; and later he would ride his bike with her sitting on the handlebars.

When I saw my father the day before he died—when he had absolutely no memory of his parents, his five sisters, his wife and his two children, his long career and marriage, and his military service, it was Claire whom he still recalled. I called Claire the day after the funeral and gave her the sad news.

Now, I will finally have the time to think back to the better years and memories, and let them drown out the recent times of struggle, sadness, and frustration.

He was a fine and honest man, a brave soldier, a successful businessman, and as good a father as anyone could hope for. May he rest in peace.

1 comment

Comment by Alan Kantor

Alan Kantor June 24, 2018 at 6:06 am

Excellent story, Robert. Your parents were the most amazing people I know. I really loved when they came over to visit my parents. I miss them so much.

Comments are closed.